My Writing Process Series

- Part 1: Intro

- Part 2: Tools of the Trade

- Part 3: Taking Notes

- Part 4: Plotting <— This Week

Howdy freeholders!

It’s time for another edition of my blog posts series on my writing process. I am going to discuss how I plot my stories today so buckle up and get ready — this is where stories are born!

Plotting vs Pantsing Discovery Writing

For a long time now, writers have been categorized into two convenient camps: Plotters and Pantsers. I can hear you now, what on earth is a Pantser?

Discovery Writing

Well, to put it simply, it was a term used to describe writers who write by the seat of their pants — ie, they have no idea where they’re going with a story, they’re just along for the ride and willing to let their characters show them what’s going to happen next.

I say was, because I’m going to stop using the term pantser right now. For my friends across The Pond, that term has an entirely different meaning. [1] In fact a lot of writers out there are ending the habit of referring to it as pantsing.

Also, I want to make it clear up front that I’m in no way disparaging anyone who writes this way — to each their own. In fact, I used to write like this (anyone who’s read my Alea Jacta Est novel will see that it doesn’t mean the story is going to be all convoluted and messed up). When I used Discovery Writing in the past, I ended up having to do a lot more work on the back end during the editing process. When I plot, on the other hand, most of the rearranging and adjusting is done before I even start writing so the process is smoother in editing (which is why I switched to plotting, because I’m not a fan of editing…more on that to come).

So what is Discovery Writing? A simple analogy is taking a road trip without a map. I’m in Dallas, Texas, say, and I want to drive to Cleveland, Ohio (because who doesn’t, am I right?) and I just get in the car and head northeast because that’s the direction I want to go. How long it takes to get there is besides the point, I’m going to enjoy the scenery, relish the journey, and see what happens.

As you’ve guessed, I may or may not actually get to Cleveland (which may or may not be a problem, depending on your point of view).

Discovery Writing is the same thing: you have an idea, and you simply start writing and see what the characters do, how the story unfolds, and where you go. A Discovery Writer may or may not know how it all ends (and therefore at least has a goal in sight) and in fact the ending may result in something the writer never even expected when they started putting words on the screen (or paper, or the recorder…you get the idea).

Some great stories are written this way, and there are plenty of excellent authors who do this. Stephen King, in his excellent book, On Writing, talks about Discovery Writing like excavating a buried dinosaur skeleton, one bone (chapter/scene) at a time. You never really know what you’re going to get until you get unearth/write it. And that’s fine — there’s a certain excitement to doing things this way and the end result is often quite a thrill for both the writer and the reader. Some people say it leads to more exciting/spontaneous stories and a richer experience for the reader.

But, like everything in life, there are other people who think the opposite is true. That’s why we have Plotting.

Plotting

What the writer does in this method is right in the name. We plot out the story, what’s going to happen when, to who, how, and so on. In our travel analogy, this would be taking a road trip from Dallas to Cleveland with a map or GPS. You can take scenic routes or shortcuts, but you know where you are at all times and where you are in relation to the end game.

Detractors of this method (who are almost universally Discovery Writers) say that plotting out the story ahead of time takes all the creativity away from the actual writing. You already figured out what’s going to happen, so the story isn’t fun to write anymore. They relish the thrill of the unknown as they write.

All well and good…until you’re happily discovery writing away and drop your main character into a corner and there’s no way to Kirk the Kobayashi Maru. [2] What happens to your character, to your story? You’ll have to go back and have the character take a different path, meaning all the work you did up to that point may be wasted (maybe you can salvage it and put it somewhere else, but that’s a job for the editing phase…did I mention how much I don’t like editing?). That adds a lot of headache and work, not to mention cussing and gnashing of teeth over the wasted effort to create that wonderful scene you now have to cut because it doesn’t work.

Meanwhile, the plotting author is happily typing/writing/dictating away, looking at their roadmap and knowing what needs to happen in each chapter. Some people take it so far as to write really specific outlines that have tens of thousands of words and dozens of pages, detailing what happens in each scene of every chapter in the finest detail. Others take the opposite approach and may write only a few words or list the name of the character that stars in that chapter.

I personally opt for another route, somewhere in between both.

The Hybrid Writer

What the hell is this then? Well, the hybrid writer takes elements from both plotting and discovery writing and mashes it all up. I am lazy, I mean efficient, and so I look for ways to do the least amount of work for the most amount of gain.

I’m not going to spend a month plotting a novel down to the last paragraph and then look at the 50 page outline and start writing a book. Likewise, I’m not just going to throw caution to the wind, wing it, and see if I can avoid massive re-writing, because that’s a risk of wasted effort I don’t want to take.

So I’ll plot my book in a specific way, writing a sentence or two with the gist of the chapter so I can get an overall look of the story and make sure all the parts are in the right order (there’s the road map). Then I’ll discovery write each chapter, letting the characters tell me where they want to go within the constraints of the basic outline I’ve written. Of course, if they want to go off-roading, I’m fine with that and will happily follow my characters beyond the horizon — and back — because with my basic outline, I’ll be able to tell really quick if I’m about to go off a cliff and stop before I waste too much effort.

This method allows me the greatest possible creative freedom, while keeping things on track, resulting in a fast, smooth writing process that doesn’t end up with a ton of work in the editing phase.

How does it…uh…how does it work?

Glad you asked. To start, I come up with a story idea. For this example, I’ll use my latest series, Ravaged Dawn, written with my writing partner, Mike Kraus. I use the same process with my solo books, but I have lots of pictures at hand for this one because it’s the most recently finished.

It all starts with an idea, the “what if” moment, if you will.

In this case, the idea was a famine strikes the United States and cripples our food production capacity. Not just any famine, but a genetically engineered bacteriophage that is designed to eat harmful pathogens that affect crops. But what if something goes wrong and it starts destroying healthy crops?

I briefly write out what I want to happen in each of the planned 6 books — the big picture event — like a sentence for each book (or so). For example…

- Book 1: The Event, and surviving the event at home, for the journey POV, figuring out what has happened.

- Book 2: Journey POV is the main star, showing trials of getting home, while MC at home is setting up shop and settling into the aftermath of The Event.

- Book 3: Journey POV is at the low point, lost friends, etc. Big fight at the homestead.

And so on. Then I focus on writing each book’s outline one at a time, starting with Book 1. I don’t actually write the other outlines until I finish writing the previous book, so I don’t waste a lot of time planning things out that change.

So, after coming up with the general idea and some place holders for Main Character One and Main Character Two (One (in this case, Pike Warren, will stay at home and Two (his wife, Abby Warren) will be on a journey to get home throughout the series), I created a list of scenes I’d like to include in the first book. I wanted scenes in the Pacific Northwest, where Abby would explore living off the land, incorporating certain ideas I had while watching the TV show Alone with my daughter. My wife and I have horses, so I of course wanted to include them in the story as well, so Marty and Luci appeared on the ranch with Pike. Many of the scenes involving the horses are taken from real life moments I’ve witnessed (the way they toss their head like they’re talking with you, etc.). And for the record, Angus, the RCMP horse, is a real horse too, belonging to a friend of ours.

Once I had a list of scenes (not inclusive, I leave space for coming up with stuff on the fly) I typically make a rudimentary grid on a piece of paper listing chapters and characters and what I want to happen to each character in each chapter.

I then transition to the Freeform App on my iPad Pro and take all the various scenes, chapters, and characters, and put them on one big page. This looks like a scrollable whiteboard, and from here I can play with different ideas, move them around and attach scenes to particular characters or not as my muse sees fit. Here’s the actual Freeform document that we worked from for Ravaged Dawn Book 1:

It looks messy because it is. At the time I created this, I didn’t have names for any of the characters, I just knew I wanted to flip on its head the standard trope of the husband fighting to get home to his loving wife who’s holding down the fort. I was determined to have the wife cut a path through the wilderness to get back to her husband and her kids and God have mercy on anyone who gets in her way.

I use Freeform as a way to spin off scenes, add scenes, delete scenes, and move them around to put them in the right order so we could get a big picture look at the whole book. Obviously, there were more scenes than this in a 100,000 word book, and I’m pretty sure there were several scenes listed that didn’t make it in the final cut for various reasons, but you can at least see how this would become our roadmap.

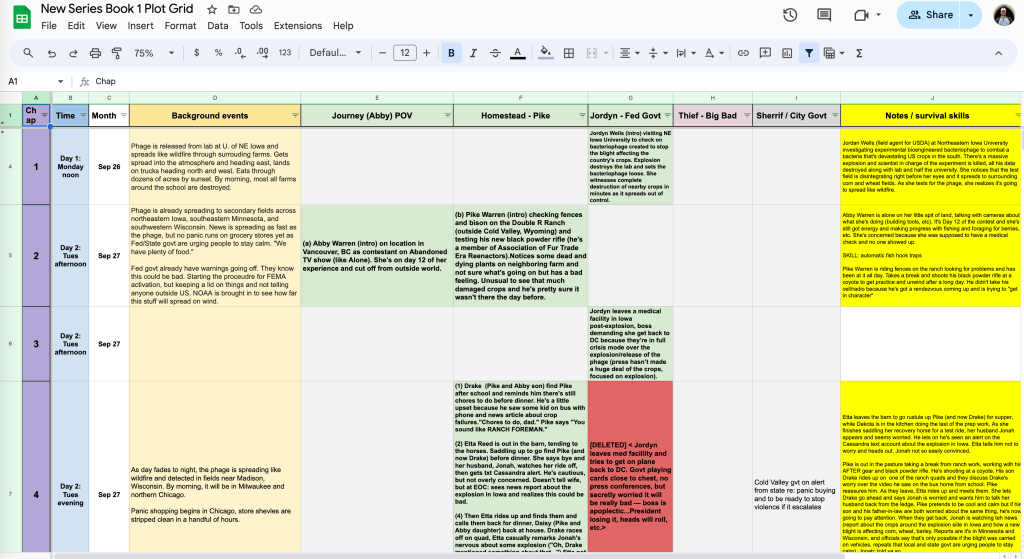

When I’m satisfied I have enough scenes per character, enough plot points and beats, I then put that messy whiteboard chart into a format I can share with my partner for review and discussion, or just organize it better for myself if I’m writing solo. Either way, this means transcribing everything on my whiteboard into Google Sheets so we can go over the details chapter by chapter.

In the above example, again from Ravaged Dawn Book 1, you can see how I plot the chapters, as we got closer and closer to actually writing the book. Each chapter (listed on the left) has a corresponding time and month when it takes place, and if a character has a part in the scene, I list what they’re doing/dealing with…along with any notes or survival skills I want to incorporate into that chapter. I also include what’s going on off stage in the background, not so much for the reader, as my benefit, so I can keep things in perspective for the characters.

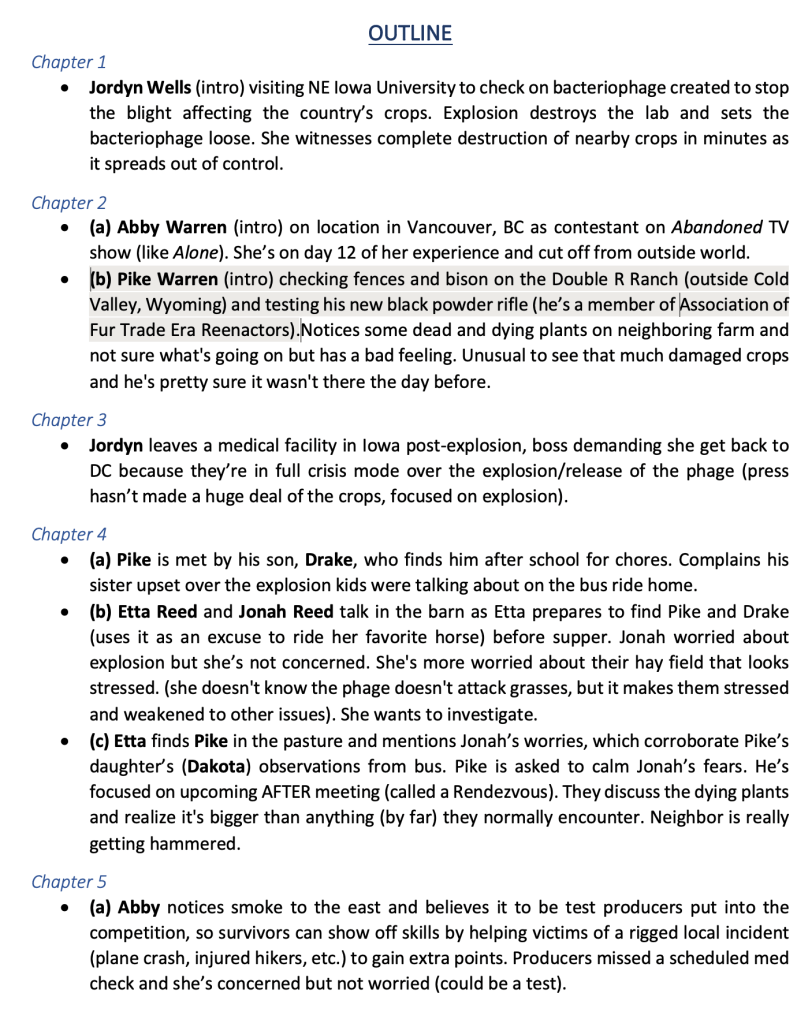

Once this plot grid outline is settled, if I was working solo, I’d start writing the book. When I work with a partner, it’s easier for everyone to translate the plot grid into a Word Document, chapter by chapter…like so:

This is the first 5 chapters in my official final outline (now included in the series story bible) straight from Word. You can see, each chapter gets a couple sentences (some are longer than others) but clearly give me the gist of what’s happening, to who, and how, without dictating exactly what happens in the chapter, so I am free to let the characters show me.

Once the whole book is outlined in this manner, and in the case of writing with Mike, and we’ve made any changes or additions and it’s finalized, I import the outline into the series bible, then get to work writing in Scrivener (which means dictating).

Here’s where the magic happens. Briefly, because I’ll get to this in a later post, I print out a page or so of the outline with the chapters I’m going to work on next, and go to wherever I need to be to dictate (my car by the river, on the treadmill, pacing in my office or bedroom, walking the neighborhood or my backyard, etc.). As I dictate, glancing at the outline for that chapter, the story comes to life in my mind and within a few minutes I’m in the zone and the outside world falls away.

It feels like I’m literally just watching a movie in my head and reporting what I’m seeing. When my timer goes off (usually I take about 8-10 minutes per chunk of text, somewhere between 1,000-2,000 words) I glance at my outline again, reset the timer and dive back into the story where I left off. Three sessions like that and I have a chapter (sometimes two if it’s a short one).

One question I have gotten frequently is why don’t I write all the outlines for all the books at once and just be done with it? Well, I tried this with my series Broken Tide. By the end of Book 1, the idea for the series had changed just enough that I ended up rewriting about 50-60% of Book 2’s existing outline to make it conform to what actually happened in Book 1.

This of course lead to an inevitable trickle-down effect, so that by the time I finished writing Book 3: Maelstrom, I almost have to completely rewrite the outline for Book 6: Breakwater. That’s a lot of writing and rewriting stuff that didn’t actually make it into any book — otherwise known as editing, which I may have mentioned, I don’t like all that much.

So, as I finish each book, I write a little summary for myself: where the characters end up, what happened to them, who’s alive, who died, who did we meet near the end of the book, what was revealed, etc., etc., etc. This note then becomes the kernel of the next book’s outline. I get a head start on the scene selection process by reading the summary from the previous book: what were the characters doing? So what happens next? That’s a scene…

Of course, then I come up with new stuff and add that in too, but having a ready made selection of scenes based on the logical next step from the previous book makes the outline creation go that much faster for each subsequent book. By the time we reach the last book or two, so many plot lines that started in Book 1 have been resolved or merged that the ending kind of writes itself.

That’s it, my secret process: Wash, rinse, repeat.

As I go along, of course, the story is going to change, so like I said, the outline is a roadmap, but it’s not the end-all-be-all to the story. I may come up with a new character or plot twist as I’m writing and then have to go back and make adjustments to the outline itself in my story bible to keep things straight. But that’s why I love this hybrid method so much…I am free to be creative on the fly, but I have a better-than-vague notion of where I’m headed, and I can keep myself on track and moving in the right direction no matter what chapter I decide to dictate, whether it’s the next one in sequence or the middle or the end.

This is what works for me, and by no means am I saying this is the only way to do it. Find what works for you and stick with it. Tweak your process as you go along — I didn’t just come up with this all in one sitting…I have changed and added to this process with each new series, adding more efficient methods of recording my ideas (from sticky notes to apps, to notes, to voice notes) and I’ll probably modify it after the next series too!

So that will do it for this time, next week we’ll talk about the First Draft, my favorite part of the writing process. Or, as I like to call it to my youngest son’s delight, the word vomit. You’ll see what I mean…

Until then, my friends, keep your heads down and your powder dry because we live in interesting times.

Notes

[1]: From what I understand, that term means someone who sits around in their underwear. In ‘Merica, pants are what we put on over our undergarments. In the UK and other parts of the (some might say, civilized) world, pants are the undergarments. Now I’m just a simple ‘Merican, so I won’t be upset if someone tells me I’m wrong, but Discovery Writing, which is the same thing as writing by the seat of your pants just sounds better, and doesn’t have any nakedness connotations, so that’s what I’m going with. I just wish there was a suitable replacement for Plotting, because it sounds like I’m in a corner twirling my handlebar mustache and laughing to myself (not that that doesn’t happen, mind you…)

[2]: The Kobayashi Maru, according to Wikipedia, was a test that cadet James T. Kirk had to complete…it was a purposely impossible situation that everyone failed, but the goal was to see how the commander reacted under stress, not whether they could solve the problem. Kirk, as Star Trek lore goes, didn’t believe in unwinnable situations and modified the test to make it winnable. Depending on your point of view, he cheated or was incredibly creative.

Leave a comment